What is Directed Content Analysis in Qualitative Research? Step-by-Step Guide

Directed content analysis is a deductive approach to qualitative analysis where you start with an existing theory or framework and utilize data to either support or build upon that framework.

Expanding, directed qualitative content analysis (DQlCA) is used to test, to corroborate the pertinence of the theory or research guiding your study, or to extend the application of the theory or research to contexts or cultures other than those in which they were developed.[1]

This is in contrast to inductive qualitative research methods—such as conventional content analysis or grounded theory—where existing theory or framework is absent or fragmented.

In this way, DQICA and deductive approaches derive codes from preexisting theory (theory-driven) whereas inductive methods generate codes directly from data (data-driven).

[Related readings: Guide to Inductive & Deductive Coding]

What is the goal of directed content analysis?

As a deductive approach, a directed approach to qualitative content analysis seeks to build upon a theoretical framework or conceptual theory. Using existing theory or research in this deductive manner helps researchers prove—or disprove—evidence for the phenomenon in question.

“Building upon” simply means the researcher intends to verify previous theories on the phenomenon in question or attempt to refute them through their own analysis.

A structured approach to qualitative content analysis

Directed content analysis is generally more structured than inductive methods in that you begin your research by identifying key concepts, categories, or themes as initial coding categories based on previous research on the topic (Potter & Levine-Donnerstein, 1999).

However, you may also edit or add codes during analysis by iteratively assessing the coding scheme. This flexibility makes it easier to offer a transparent chain of logic in the write-up that explains what drove the changes to the research approach and how those changes enriched your ultimate conclusion—increasing the reliability and trustworthiness of the final results.

In the end, the goal of DQICA is to identify core categories and themes from previous studies and use them as coding guidelines to analyze source materials and build upon a phenomenon.

When should I use directed content analysis?

DQlCA is a reliable and transparent qualitative research method that can increase the rigor of data analysis and allow the comparison of the findings of different studies. Considering the increasing amount of knowledge and theories based on inductive content analysis, DQICA provides a particularly useful method to test these theories. (Assarroudi et al., 2018).

For more concrete use cases, you should consider directed content analysis when:

You have an existing theory or framework you want to build upon.

You want to offer supporting or non-supporting data of a theory.

To underpin qualitative research conducted through inductive analysis.

To categorize all instances of a particular phenomenon within your samples.

You want to analyze large amounts of data—usually textual data.

Source materials for directed content analysis

Directed content analysis can be used to analyze any occurrence of communicative language that is presented in a textual format. Data sources include but are not limited to the following:

News articles

Textbooks

Journals

Transcribed documentaries

Transcribed news stories

Survey research

Poems

Essays

Research field notes

Social media

What is the step-by-step process of directed content analysis?

In the study “Directed Qualitative Content Analysis (DQlCA): A Tool for Conflict Analysis”, Kibiswa (2019) explains that DQICA has three main phases: preparation, organization, and reporting. The following is our summary and interpretation of her research framework.

Tl;dr version

First, develop the study’s framework and operational definitions based on previous theory. Next, pick the unit of analysis and sampling materials you will analyze. Immerse yourself in the data by reading and re-reading the texts. Then, code and organize your data to make connections, interpret them, and draw conclusions. You then create a clear, logical outline of the research process to further enhance reliability. Finally, describe the research process and your findings.

Phase I: Preparation

1. Develop the code framework & operational definitions of the study

Identify themes and subthemes within the previous research or studies that you want to test or verify. Basically, you develop the guiding framework for your study in this step.

The goal is to categorize the theory-based themes from other studies into a structure analysis matrix to help define what you will code, which is often a matrix that contains operational definitions of each theme and category you plan to code for.

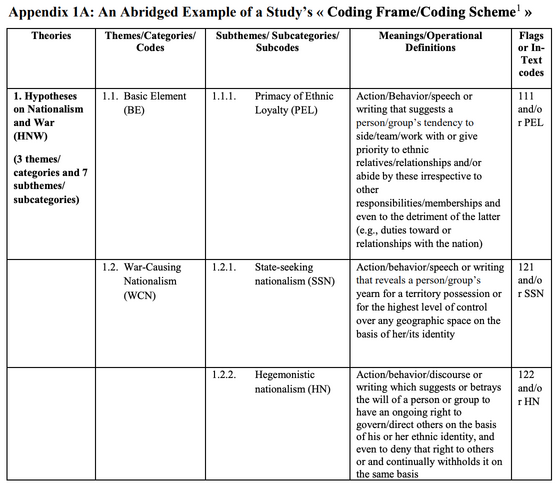

Kibiswa exemplifies this step in the appendix of her study as follows:

The codes and their corresponding definitions based on theory-based themes and categories will later lead the researcher's work in subsequent steps of analysis. [2]

2. Determine the sampling materials

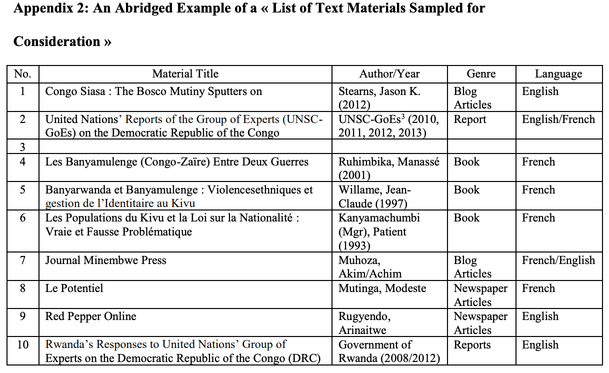

Now that you have (1) identified the pre-existing theory, (2) defined the basic focus of your study, and (3) defined the themes you will explore, the researcher needs to decide what materials to analyze in order to reach the study’s goal. [1]

For example, the samples selected and their presentation in Kibiswa’s study:

You can choose one or several of the source materials listed in the section above. As DQICA is deductive in nature, the sampling strategy must be purposive (units selected are related to your study) in order to confirm or refute the specific theory-based themes guiding your study. This is an iterative, cyclical process of data collection and data analysis where you may add supporting data as you go.

3. Immerse yourself in the data

With the materials selected, you read and re-read them. This starts by searching and locating the themes and categories from step 1. Here, you read through a literal, manifest lens in order to get a sense of or make sense of all the materials at a top level.

While reading a selected text, highlight all chunks that are related to your study. You can do this by hand or more efficiently and organized with CAQDAS software like Delve.

The result of this iterative process is a text or document containing the various texts’ meaning units (themes from step 1) highlighted and color-coded. Each highlighted chunks represent one theme or category chosen earlier.

Phase II: Organization

4. Code & organize the data

Now you re-read the materials again. Here, you assign the codes from step 1 to each chunk of text you highlighted in step 3. This is a process of refining your data.

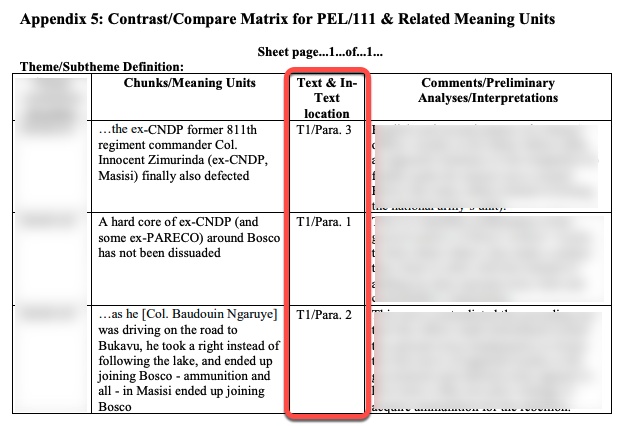

This pass should be interpretative and reflexive to help organize the results of your previous readings. You want to start interpreting your data collected to this point with memos attached to each chunk of text with clear reasoning of why it was selected. You may also refer to the location within the specific sample where it occurred to provide a quick reference for you or the reader—as depicted by Kibiswa.

In addition, Kibiswa looks for any data that challenges the theory under study—or that conflicts with the pre-defined operational definitions. These are negative cases that you may use in the following steps to adapt or reinforce your eventual findings, as shown.

5. Draw conclusions by making connections between data

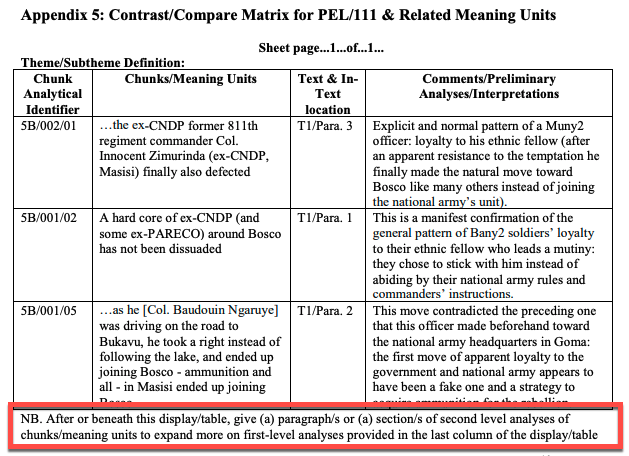

Next, you generate meaning, make reasonable inferences, and go deeper into what the data is suggesting on a latent content level. Kibiswa refers to this as the first-level (manifest) and second-level (latent) analysis and presents the steps in consequential order as follows.

This includes building a logical chain of evidence, contrasting/comparing text passages with theory-based themes at the manifest and latent content levels, and offering explanations of how you arrived at those conclusions. [1]

This may include determining possible new themes that did not fit into any predefined options that enrich the initial research framework. You can use the negative cases from step 4 to verify if they fit into the narrative or conflict with the findings gleaned here.

According to Kibiswa, the result of this step is that you “make explicit latent content” and also begin to form an idea of how to explain your data to the reader in a narrative format.

6. Substantiate your interpretations

Explain your study findings and provide comprehensive details about the analytical process and research decisions that lead to those findings.

Where possible—and to improve the reliability of your study—provide quotations, appendices, and tables (such as your operational definitions from step 1) that support your interpretation of the data and your findings. Negative cases are also helpful here in order to support your claims or show they may have some limitations.

The goal of this step is to provide a way for the reader to understand how you arrived at your conclusions and form their own opinion on their validity and trustworthiness.

Phase III: Reporting

7. Create an outline to present your conclusion

Now, you present your initial research plan along with an in-depth explanation of your research process. Did you encounter contradictions within your research framework that altered the coding scheme? Were there alterations to your understanding of the theory upon which you based your research? Here, you write out and explain these decisions.

8. Write your final narrative

Tell the complete story of the data you collected and how it relates to your initial operational framework. Show how the data you collected validated or invalidated pre-existing theory, and elaborate on anything new that builds upon that framework.

Use Content Analysis Software

The best software for content analysis is the Delve qualitative analysis tool. The software will help you through every stage of the process. After identifying your framework of choice, you can translate that framework into a Delve codebook. Then you’ll import text files into Delve, and use intuitive coding features to apply your codebook to the text.

Memos are an important part of your analysis and reporting for content analysis. They also help organize your research approach and undersatnding of the samples. Conducting your content analysis with pen and paper requires manually writing memos and attaching them as needed.

With Software such as Delve, all-important memos are never lost and are easy to track with time-stamped records. You can also track how codes correlate to descriptors or attributes.

Delve is cloud-based, collaborative and easy to learn. It includes free tutorial videos, responsive customer support, and flexible payment options. It’s the #1 ranked Qualitative Data Analysis software.

Qualitative analysis doesn't have to be overwhelming

Take Delve's free online course to learn how to find themes and patterns in your qualitative data. Get started here.

Directed content analysis is just one approach of many ways to analyze qualitative research. To read more about other types of coding, read our Essential Guide to Coding Qualitative Data.

Request a Demo For Delve Content Analysis Software

Online software such as Delve can help streamline how you’re coding your qualitative coding. Try a free trial or request a demo of the Delve.

References

Kibiswa, N. K. (2019). Directed Qualitative Content Analysis (DQlCA): A Tool for Conflict Analysis. The Qualitative Report, 24(8), 2059-2079. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3778

Elo, S.; Kyngas, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008.

Potter, J., & Levine-Donnerstein, D. (1999). Rethinking validity and reliability in content analysis. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 27(3): 258–284.

Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, Ebadi A, Vaismoradi M. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs. 2018 Feb;23(1):42-55.

Cite this blog post:

Delve, Ho, L., & Limpaecher, A. (2020c, September 03). Step-by-Step Guide: What is Directed Content Analysis in Qualitative Research? Step-by-Step Guide https://delvetool.com/blog/contentanalysisdirected